(This is a slightly edited version of a presentation I gave at Glasgow International Fantasy Conversations 2018, a two-day conference with the theme of ‘Escaping Escapism’. This post contains massive, massive spoilers for Star Wars: The Last Jedi. You have been warned.)

So, hot take time: Star Wars: The Last Jedi is a post-secular examination of what it means to be a person of faith confronting the oppressive history of one’s religious tradition. It’s also highly instructive for finding a way of reading fantasy texts theologically without invoking the discourse of nostalgia that the genre has historically been associated with. This presentation will consider The Last Jedi‘s metafictional commentary on Jedi lore as a model for radically re-thinking how we engage with with mythic and fantastic narratives in religious and theological contexts. But before we delve into a reading of the film proper, it’s important to give some theoretical and discursive context.

A long time ago in a discourse far, far away….

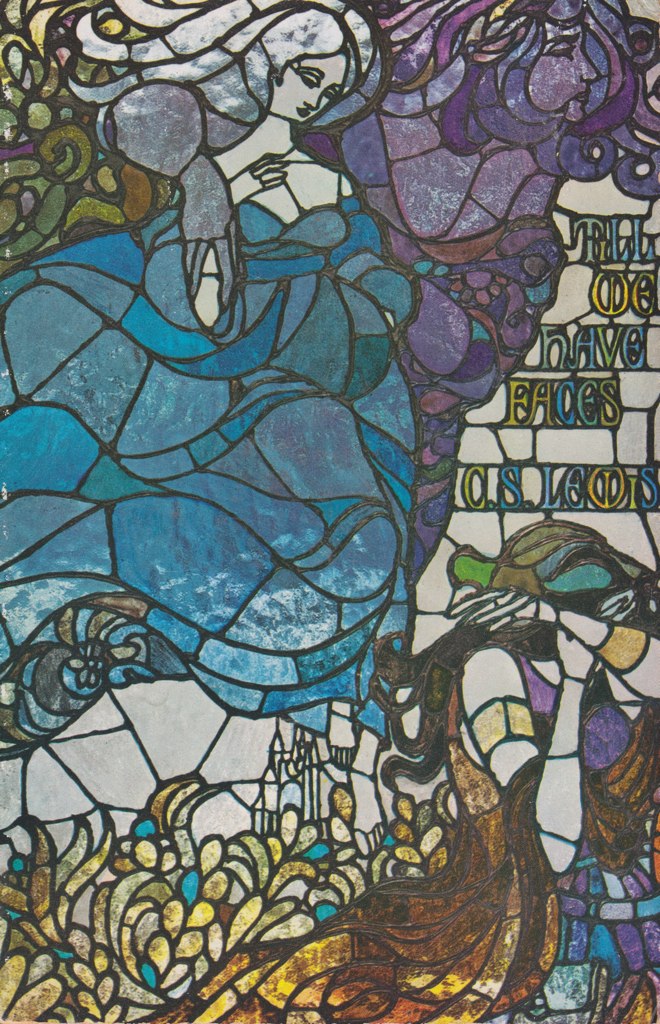

The fantasy genre is commonly associated with theology, but this association has largely relied heavily on assumptions of archaism and nostalgia up to this point. Much theological scholarship on fantasy takes cues from Colin N. Manlove’s claim that ‘[f]antasy often draws nourishment from the past […] particularly from a medieval and/or Christian world order […] [I]n fantasy the direction of the narrative is often circular or static’ (Manlove 1982, 23). (I’ll just offer a side note here to appease my medievalist friends and colleagues that fantasy’s engagement with the medieval is heavily contingent on modern understandings of that world order, regardless of accuracy.) Although Manlove wrote this in 1982, this mode of approaching religious fantasy texts has remained largely unchanged within certain corners of the academy and pop culture. Readings of the fantasy writing of authors such as C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien as religious apologetics and/or a retreat from the trauma of modernity into a more hopeful archaic world order are practically a cottage industry (although again, I would argue that even these readings are a bit reductionistic!).

Yet in the West’s current political climate, which in the past several years has seen the rise of regimes that openly attack populations that were already marginalized at best–often (especially in the U.S.) couching this violence in religious terms–it’s necessary to reconsider this view. We need, as Rose Tico encourages Finn to do on the planet Canto Bight, whose opulent wealth masks the violent and oppressive means by which it is attained, to ‘look closer’ and ask who is marginalized and excluded by our nostalgic escapism. As Marcella Althaus-Reid puts it, ‘the location of areas of exclusion in theology is one of crucial importance; for instance, poverty and sensuality as a whole (and not as separate units) has been marginalized in theology’ (Althaus-Reid 2000, 4).

For Althaus-Reid as a queer Argentinian woman, this means that we need theology that proceeds from the struggles of women, poor people, queer and trans people, colonized people, and especially people who live at the intersection of these oppressed identities. Moreover, we also need ways of narrating these theologies without falling back on a monolithic–or indeed monomythic–grand narrative.

What does this have to do with space wizards?

Although Star Wars is technically a sci-fi/fantasy hybrid (that’s a whole other can of worms that we don’t have time to get into), we can see the impulse toward nostalgia at work throughout most of the saga. George Lucas and his collaborators famously modelled the narrative of the original trilogy after Joseph Campbell’s archetypal ‘monomyth’, and the films visually evoke cinema from bygone eras such as sci-fi serials, samurai epics, and Westerns, to name just a few. The narrative structure of the series has likewise tended toward stasis; in one now-infamous soundbyte from the making-of documentary of The Phantom Menace, Lucas proclaims, ‘It’s like poetry, [the films] rhyme.’ 2015’s The Force Awakens introduced new characters, but largely initiated a cyclical repetition of the original Star Wars trilogy, perhaps partly to reassure fans after the disappointment of the prequels. All of this establishes a narrative pattern in which the status quo is repeatedly disrupted only to then be heroically restored, which is mirrored in-universe by the emphasis continually placed on bringing balance to the Force.

The Last Jedi, meanwhile, signifies a break with this pattern and with many of the tropes and narrative devices that characterize the saga in the eyes of many fans. To say that this has been a controversial move would be an understatement, since in many ways the film can be read as a metafictional commentary on the Star Wars universe’s lore and themes.

The film opens where The Force Awakens left off narratively, as our hero Rey journeys to the remote planet Ahch-To in the hopes of training as a Jedi with Luke Skywalker and convincing him to aid the Resistance in their struggle against the fascistic First Order. She finds, however, that Luke has renounced the Jedi ways and is unwilling to help her, save for three lessons about why he believes the Jedi religion ought to die with him. In all of these lessons, fan perceptions of the expanded Star Wars universe become in-universe lore that is rigorously critiqued and revised within the film.

Lesson I: The Jedi do not own the Force.

Rey’s initial understanding of the Force may mirror the perception many fans came away from the original trilogy and even (especially) the prequels with. When Luke questions Rey what she knows of the Force, she responds, ‘It’s a power that Jedi have that lets them control people and make things float.’ This is a moment of comic relief in the film, but it also signals that up to this point the Force has been associated with mastery, domination, and control belonging to a select group of people.

Luke corrects this assumption. As he puts it, ‘The Force is not a power you have. It’s not about lifting rocks. It’s the energy between all living things: the tension, the balance that binds the universe together. […] And this is the lesson: that Force does not belong to the Jedi. To say that if the Jedi die the light dies is vanity, can’t you feel that?’

This instantly democratizes the Force, and the implications of this extend to the film’s rejection of the rest of the saga’s obsession with prestigious bloodlines. While the previous seven films tell the story of simultaneously the most powerful and most dysfunctional family in the galaxy and their respective destinies, The Last Jedi deliberately subverts this in favour of a heroine who is well and truly from the margins of society. Rey, who has spent a film and a half obsessing over her mysterious parentage, is forced to confront the truth that there is no mystery. Instead of the heir apparent to a powerful lineage, Rey is the daughter of, in Kylo Ren’s words, ‘filthy junk traders, who sold [her] off for drinking money’. Her parents are ‘dead, in a paupers’ grave in the Jakku desert’. Rey is nobody, from nowhere, and as Kylo Ren–that is, Ben Solo–rightly identifies, she, unlike him, has no pre-ordained place in the grand narrative of the Jedi against the Sith. Instead, she is left to find her own place in the story.

This revelation upends our understanding of how this universe works, and throws into question everything that came before it. In fact, the character most obsessed with blood relations, lineage, and destiny in the film is Supreme Leader Snoke of the First Order, which brings to light the fascist and eugenicist implications of this ideology and also leads to his downfall. Snoke is so fixated on where everyone fits into the grand narrative that he doesn’t anticipate his apprentice turning against him and killing him. This leads us to…

Lesson II: Your space wizards are problematic.

Luke again: ‘Now that the Jedi are extinct they are romanticized, deified. But if you strip away the myth and look at their deeds, the legacy of the Jedi is failure, hypocrisy, hubris. […] At the height of their powers they allowed Darth Sidious to rise, create the Empire, and wipe them out. It was a Jedi Master who was responsible for the training and creation of Darth Vader.’

The Jedi may eventually have been destroyed by the Empire, but Luke suggests that their close association with the Old Republic, and their failure to sufficiently challenge that existing power structure, rendered them complicit in the Empire’s rise. Luke thus re-contextualizes the old Jedi Order as what Althaus-Reid has called ‘High Theology: an imperial enterprise, the art of android epistemologies but not of humans […] which allows theology to perpetuate itself (resurrect) through what we have called the decency mechanisms, of Black, Liberation, Aboriginal or Feminist theologies alike’ (Althaus-Reid 2000, 91-92). It’s hard not to hear Luke’s words and reflect on the various think pieces written by American evangelicals and Republicans disavowing Donald Trump in the wake of the 2016 U.S. Presidential election and longing for a return to normalcy or ‘sanity’ within their institutions just as many in the Resistance of Star Wars desire a resurrection of the old Jedi Order.

What both Luke and Althaus-Reid point out, however, is that theology and religious institutions are often complicit in the creation of empire. Trump’s rise to power, for instance, was in part an effect of white American evangelicalism’s understanding of divine power, dominionism, and heterosexual masculinity, and the complex ways these things interface with the Republican party’s economic and socio-political agenda. Althaus-Reid, however, takes this a step further in pointing out that theological tropes that uphold hegemony and empire can manifest in the resurfacing of grand narratives and respectability politics even in theologies from the margins and ‘[succeed] in killing us’ (Althaus-Reid 2000, 92) all over again.

Once again, we can see this playing out in where The Last Jedi takes Luke as a character. It may have been a Jedi who saved Anakin Skywalker from the Dark Side, as Rey reminds Luke, but his attempt to resurrect the Jedi Order merely duplicates the old structure in ways that have both systemic and interpersonal consequences.

Lesson III: Luke is complicit.

Luke’s endeavours to train a new generation of Jedi see him sliding into religious fanaticism. The openness, vulnerability, and compassion he showed toward his father which allowed him to turn him away from the Dark Side give way to a dogmatic adherence to a strict Light/Dark binary regarding the Force, which finally mutates into paranoia about the Dark Side. He senses the darkness in his nephew Ben Solo and is tempted to murder him. Luke’s fear of the Dark Side allows the Dark Side to take hold in him for long enough to drive Ben over the edge. Traumatized, Ben turns fully to the Dark Side and becomes Kylo Ren.

So where do we go from here?

Reflecting on the oppressive histories of Western Christianity in our world and the Jedi Order in the world of Star Wars, one temptation would be to disavow religion and theology completely. We see this reaction in both Luke and Kylo Ren. Kylo Ren’s philosophy is to ‘[l]et the past die. Kill it, if you have to.’ Kylo Ren razes Luke’s new Jedi temple to the ground, killing all but a few students, and after killing Supreme Leader Snoke, installs himself as the leader of a fascist regime. Meanwhile, Luke Skywalker’s solution is repression. Lots and lots of repression. He severs his connection to the Force and attempts to burn down the library housing the sacred Jedi texts.

The problem with both of these approaches is that they are both purity discourses that fail to adequately address the heart of the problem, and once again maintain oppressive hierarchies while outwardly disavowing them. Luke Skywalker and Ben Solo are both men from a powerful family who continue to benefit from their problematic heritage even as they attempt to shed the trappings of it. (We see this happen literally with Ben, who first changes his name and later destroys his mask, but refuses to give up his powerful position even when Rey provides him ample opportunity to do so.) This once again brings to mind Althaus-Reid’s words when she notes that ‘[t]he problem is that it is easier to live without God than without the heterosexual concept of man’ (Althaus-Reid 2000, 18).

Dismantling toxic white imperialist masculinity is a difficult responsibility, and one which both Luke and Kylo Ren try to abdicate. Kylo Ren attempts to escape the abuse inflicted on him in the name of the Jedi Order and protecting the Light, but ultimately replicates abusive patterns in the violent and nihilistic means by which he attempts to overcome his trauma. The ambition he expresses to Rey is a vision to transform the galaxy, but it’s a world order in which he would still be at the top of the hierarchy. Luke, meanwhile, wallows in self-pity and resentment of his status as a legend, and thus fails to be of any help to his allies or of any emotional support to his friends and loved ones when they need him.

Thankfully, Rey, in her need to give some structure to her connection with the Force, sees a different way forward. She cannot ignore, for instance, the voices that call her by name to the Jedi library, but neither is she afraid, as Luke is, of the cave of dark energy beneath the island. As she says to Luke, ‘[t]he galaxy may need a legend,’ but she also recognizes that it will require a different way of relating to that legend than what came before. Before she leaves Ahch-To, Rey takes the sacred Jedi texts with her unbeknownst to Luke and stows them aboard the Millenium Falcon as she journeys to aid the resistance.

Meanwhile, Yoda shows up in Force-ghost form to burn down the library while telling Luke, ‘Heeded my words not, did you. “Pass on what you have learned.” Strength, mastery … but weakness, folly, failure also. Yes, failure most of all. The greatest teacher, failure is.’ In this scene, Yoda’s words come very close to those of queer theorist Jack Halberstam, who posits that ‘[u]nder certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world’ (Halberstam 2011, 3).

At the end of the film, the battered remnants of the Resistance are housed on the Millennium Falcon, meaning that the sacred Jedi texts are now in their midst. Rather than being sequestered away in a library in what Luke calls ‘the most un-findable place in the galaxy’, the Jedi texts now exist among the downtrodden and marginalized, those struggling for their ability to exist in a hostile political environment. While Rey remains committed to carrying on the Jedi tradition, the institutional structure in which it was formerly housed has quite literally burned to the ground, leaving her to re-invent it on her own terms.

There may be a fun scriptural allusion to be made here about the sacredness of things which burn and yet are not consumed, but there seems to be something a bit more going on here than even that. The final scene of the film depicts several enslaved children on Canto Bight sharing the legend of Luke Skywalker and the Jedi, before revealing that one of the children has a connection to the Force. It’s a testament to the potential of legends and religious narratives to provide the oppressed with tools to resist and liberate themselves from their oppressors, though exactly how remains yet to be seen.

Or, as Margaret Atwood put it in The Handmaid’s Tale: ‘The Bible is kept locked up, the way people once locked tea up, so the servants wouldn’t steal it. It is an incendiary device: who knows what we’d make of it, if we ever got our hands on it?’